I'll follow you: Finale

Now you've seen the Captain, and met the crew, it's time to dive deeper into what would be the first operational flight for five of them, and the last operational flight for two.

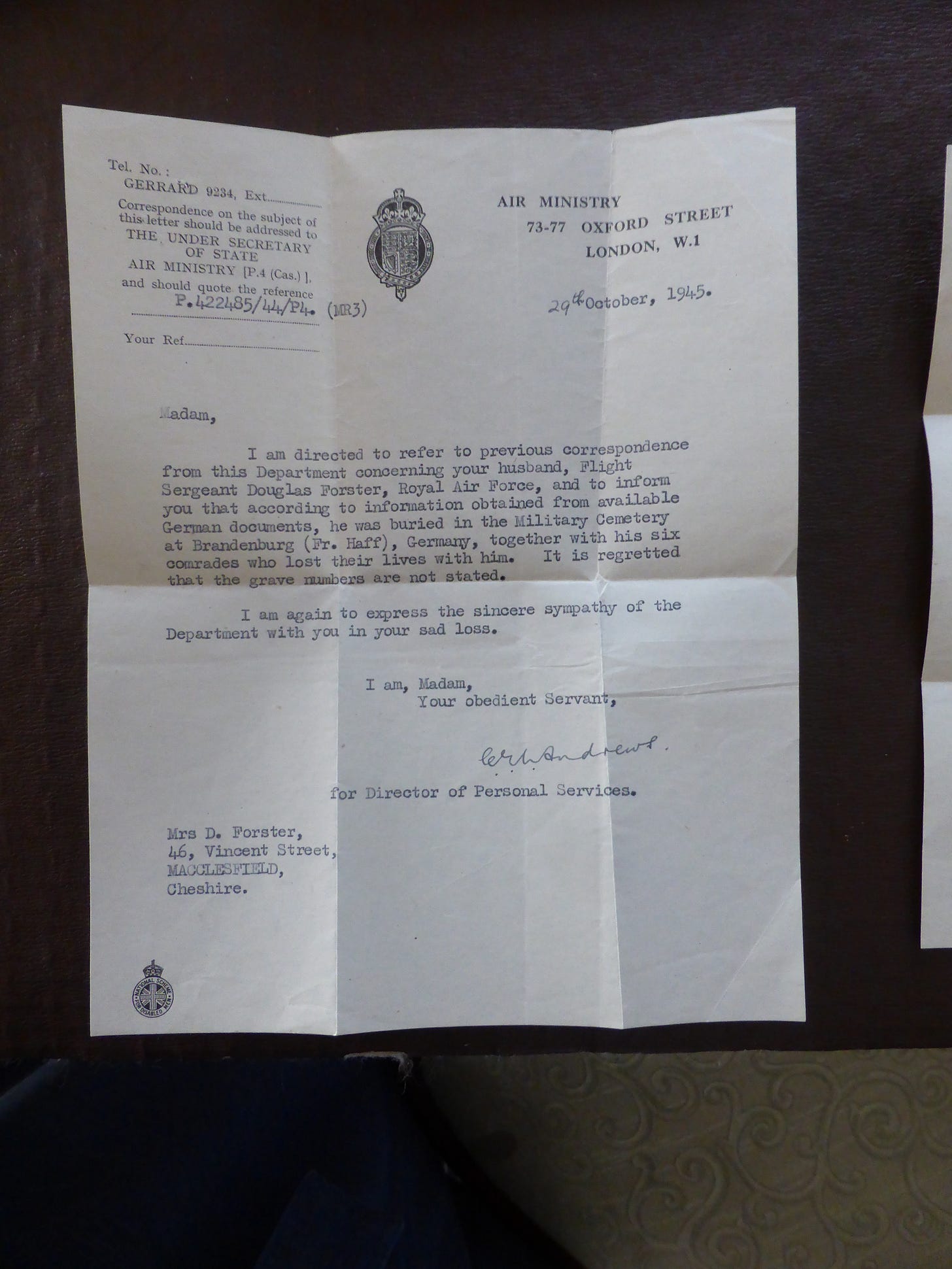

That is the final official document their names are stated on. I’ve found it in Henry Carter’s service record, and it made my stomach turn. There’s nothing worse for a grieving relative that seeing this line - having no known grave. That means, no saying goodbye. That means no visiting. That means no closure. And that was everything the families got left. That, and…

Mrs. McKechnie got the similar letter, but there, there was no mention of all seven being identified and buried. Moreover, there was a typo in the name of the crash site. Mrs. Carter, along with the rest of wives, mothers and sisters, was also promptly notified of the death of her boy. The letters from the Air Ministry went on and on, coming year after year, till the end of the fifties, when it was finally attested, that there could be no grave certification or - talk of returning the boys home. Brandenburg by that time had lost its name to a less musical Ushakovo, and the whole region was now Soviet-occupied. And, of course, no Soviet military would have any foreigners on the site. So, the relatives had to lose all hope.

What led to all that, is very clear now, after countless times of going over the tragedy. I must thank John Wilson for supplying me with maps and letters, and to Alan Wells for sending me records and details on the raid.

That day, 28th August, was the day of preparation at all Lincolnshire bases. The crews were getting ready to fly again, with the more precise targeting, to the most dreaded destination, a place they would rather evade than invade - Koenigsberg, the golden apple and a pain in the neck for Germans, Soviets and the British, thanks to the constant pressure of ‘Father of peoples’ and ‘The Greatest Leader’ of them all. For Hitler, Koenigsberg was a much cherished spot, a cradle of German culture, tradition and a valuable asset, as well. For Stalin, who, like his adversary, never cared much of the people, Koenigsberg was a point-fixe. He needed the Baltic all to himself, and he wanted it badly - at whatever the cost. As for Churchill, he was the only one who saw the situation for what it was - a very risky business, full of obstacles and imminent losses. He knew too well how hard it would be to fly all the way there (about six hours) and back risking all the time. By 1944 he finally agreed - and two consecutive raids were planned. The first, on 26/27 August, was not as successful, with mixed-up targets and visibility issues, but at least, the losses were not as great. Remember Les Boivin? His crew flew that night, and succeeded in coming back. He must’ve groaned when he heard of a second raid, planned for the 29th - that meant one more sleepless night, preceded by a 4 -6 hour drilling. All crew had their own briefings, a short rest and then the scramble followed, scheduled for the interval of 19.35 to 21.00.

McKechnie’s crew was scheduled for 20.35. That of course means that Neil had to mentally prepare for the long flight there and back, and pray he would come back. By 1944 the Nachtjagd, ever-watchful German night shooters, grew restless, vicious and deadly. Their lives were not that easy, I must say, and they were mad at the British pilots, who looked better, ate better, and, to the general understanding, slept more. After the first raid, that was a bit of a surprise, the second one would be deemed successful, but devastating, with at least fifteen crafts lost.

However, they took off.

Visibility was fine, but the radar silence was on to prevent the Germans from catching the whiffs of banter - it broke only when they reached the neutral Sweden. That was, I think, the very moment they were overheard. What they didn’t know, was that the city wouldn’t be taken by surprise, as the last time.

The Lancs were met with blinding red and green lights, by flac - and the Nachtjagd, who were waiting for a chance to shoot down the bomber boys. Besides that, a delay in bombing ensued, and they had to circle the sky in wait for a signal. For some, it proved too hard a task. They knew too well that it was a double risk - they were already seen, and the fuel could run dry faster. And that spelt possible issues with coming home.

Knowing the sort of man that McKechnie was, he probably decided to load off quicker and leave faster, hoping they would have a chance to fly past unnoticed. This decision would prove disastrous, but he had his reasons.

I have mentioned Neil suffered from chronic air sickness - well, that was a major issue for him for all his life. There would be no treating it - the only medicine they could come up with at the time, would be anti-histamine with a dash of tranquilizer, but that as you see, was a no-no for a bomber pilot. Too risky. What else could the doctors suggest?

For one, eat lightly. Then- good rest, preferably for a day before the flight. Then - nicotine. Yes, that would be quite popular. Since the early 1920s it was believed that smoking could relieve many a thing. Cigarettes and tobacco were included in soldiers service kits since the WW1, and RAF pilots were smokers generally. McKechnie couldn’t smoke on board - but he could’ve had a couple of smokes before. As for eating lightly, that would be too much, especially for a flight that long. Rest was also a luxury. McKechnie had to suffer in silence. You might say, he could stay put - and that would be exactly what his elders thought. He was known for perseverance and excellence, it’s true, but also, he could be a real pain when it came to rules and regulations. He wasn’t a rebel, per se, being a highly disciplined professional, but at times, his Scottishness kicked it and he flew with a sprogg crew again.

If you think that air sickness is simply being nauseous for a time, you may be only half right. In its chronic form, it may be disastrous. Let’s go over the basics first.

Airsickness is a particular type of motion sickness that is common for many new pilots. For new pilots, it can happen often early during flight training sessions, as your body adapts to the flight movements.Many people experience it while flying, but the good news is that it can be overcome. Let us begin by understanding the cause of airsickness.

The Cause of Airsickness:

Airsickness is the reaction of your body while it’s trying to interpret different signals. While flying, your central nervous system senses the movement whereas your brain interprets no movement or a lack of movement based on what your eyes see.

While flying, your eyes tend to adapt to the movement as if you’re not moving. However, your inner ears sense movements in upward, downward, left and right directions. It reacts to the movement in association with gravity and informs your brain what it is sensing. This creates a conflict of signals that confuse the body. When this happens, you might feel nausea along with a range of other symptoms.

Symptoms of Airsickness:

Nausea

Vomiting

Fatigue

Disorientation

Chills

Queasiness

Headache

Sweating

Dizziness

Increased Salivation

Some pilots are more susceptible to airsickness than others. For instance, as I mentioned above, training pilots that are new to the flying environment. Moreover, pilots that are not flying the plane such as flight instructors might also be susceptible to airsickness. This could happen because their attention is not towards flying the aircraft but rather on the student. It has been observed that focusing on flying duties can relieve or in some cases even prevent airsickness from occurring.

Listed below are things that could make you susceptible to airsickness:

Fatigue

Medication

Illness

Alcohol

Stress and Anxiety

Emotions

Why am I that fixed upon that detail? It’s quite simple. McKechnie was wound up that night. First, he didn’t have much sleep. He was overworked, tired, probably hungry - and immensely stressed due to the delay in bombing, the skies bright with searchlights, and nervous exhaustion in general. That, for him, meant one thing - he was getting worse. The crew didn’t know the extent of his trouble - only Clarke, being closer than the rest, could’ve noticed the pallor, nervousness and fading concentration. Moreover, nausea really became stronger, and the flight was turning into a torture. Add to that some chest compressions, feeling of being choked up, and headache.

And, the decision to change the route a bit, was made. They would turn SW, and soon enough, a signal would come from Collins - bandits on six, nine and three o’clock. They were being cornered, and there was no escape. Blinding lights searched the sky, and there was no seeing straight. Later on, Germans stated that no shooting took place, and they just coned the JB593, blinding them and making them land. If so, the information in the British records, must be wrong, as it states ‘shot down and exploded on impact with the ground’. But that, again, would make it impossible to identify and bury seven bodies.

There was no explosion.

Analyzing that, I have to side with repeating German records, that all state that JB593 was coned and blinded at Pokarben, 4 km East of Brandenburg, at 1.20 am.

The landing was harsh, due to unknown terrain, piles of rubble, and proximity of trees and water. You see, Pokarben - just before the war - was a farm, with a vast territory, large orchard and a pond - or a lake. Moreover, the river wasn’t that far. It was deserted and fell into disrepair, and the Germans, who had a base at Brandenburg, must’ve thought this to be an ideal coning spot. However, JB593 was not the only Lancaster ending up there - LM278 was also lured there on the 27th. The only survivor was Henri Souci, who inspite of his bad condition, identified his crew to his best ability.

Now, McKechnie couldn’t have known that the remains of LM278 were still there, mere 250 metres away - and he did his best to concentrate enough. But airsickness took the reins. The fatigue, stress, nervousness and changing altitudes made him lose concentration. I somehow think Clarke noticed that and tried helping him out, but it was too late. They landed, probably sliding and then there were trees.

The impact was nearly fatal and harsh. McKechnie probably fainted and was knocked out, jamming into the dashboard. Clarke, who wasn’t even secured, due to his seat being a flexible one, met the same fate. Same goes for Fletcher, who, as aimer, was lying flat on his stomach in his capsule. The rear end, as it was with several other cases, could have fallen off, jamming poor Collins. As for Carter, Forster and Jeffrey, I suspect they’ve had concussions or were hurt during it all.

They were coned at 1.20, and found in early morning on August, 30. The Germans examined the site, identified the bodies - it wasn’t that difficult, with all the insignia and tokens they had on, and gave the case a code that would later prove useful - KE9585. McKechnie’s cufflinks with RAF wings and a mysterious ring were found- or taken, and put in a box with the same code. How do I know?

Despite the popular prejudice, the Germans were not barbarians. They respected the British, and moreover, they had an order from Goering himself - to bury the crews in an orderly fashion. The bodies were respectfully taken to Brandenburg where a beautiful church stood. The local churchmen were not that keen to welcome enemies to their cemetery, but the order is an order, and they were given a Christian burial. Years later, a German officer would sketch the map of the burial site. He did have a sharp memory, that guy.

You might think it is the end. But the end isn’t yet there.

Since 1945, the British tried visiting the place. For almost five decades they were refused on different grounds. They almost did come, in Yeltsin and Gorbachev’s time, but the country was a bit unstable, so again, to no avail. As the regime changed, it was getting clear that nobody would ever permit the visit or commemoration. There was, however, a memorial dedicated to those who were claimed by the Baltic, and the Bomber boys were all there. It was back in 2001. In 2006 the memorial got its renovation and all the names magically vanished.

The church at Brandenburg, however, still stands - and it reminds me of Glastonbury Tor. That’s it before the war, by the way.

That’s what we got now. The church suffered during the siege of Brandenburg, and they was lovingly picked apart by the newcomers. What a great way to show appreciation!

That’s it now. Honestly, it has a very strange and difficult energy, this place. I almost fainted passing by. But that’s a tale for another time.

My boys are still there. Now that I know it, I feel strangely calm. I know they haven’t been troubled, they’re at peace. And that’s my limit at the moment. I only wish that at Metheringham, they would preserve the real story, instead of making info shields with empty words like ‘no known graves’ and ‘tragically lost’. There are people behind the names. You owe them. Make them proud.

‘